Dramatic comebacks were the rage in the state of Missouri during the autumn of 2011. The baseball world marveled at how the St. Louis Cardinals, 10 and a half games out of a playoff spot in late August, rallied to win one of the greatest World Series in history over the Texas Rangers, including a scintillating Game Six victory in which the team was twice down to its last strike, in consecutive innings, before rallying to win.

|

| Photo courtesy of Sam Varnhagen/Ford Motor Co. |

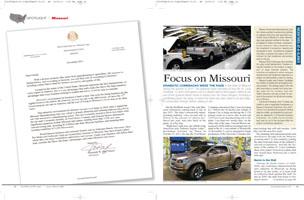

But the Redbirds weren’t the only Missouri institution coming back to life in late 2011. The state’s automobile manufacturing industry, once second only to Detroit in the amount of vehicles produced per year, was also back in the game, in a big way.

“Right here, right now, the rebirth of the American auto industry begins today!” proclaimed Governor Jay Nixon on October 21, 2011, the day the Ford Motor Company announced that it was investing $1.1 billion into its facility just outside of Kansas City to begin producing the F-150 pickup truck in a move that would add 1,600 new local manufacturing jobs at the plant. Less than two weeks later, on the other side of the state, General Motors announced a $380 million investment into its plant in the St. Louis suburb of Wentzville on November 3, a move designed to begin production of the Chevrolet Colorado mid-sized pickup that will add another 1,660 jobs over the next five years.

The stunning twin announcements sent shockwaves through both the Missouri economy and U.S. auto industry, putting the state front and center in the industry’s national revitalization. And like the fortunes of the cardiac St. Louis Cardinals, these were major victories in a place that few would have believed just a short time ago.

|

| Photo courtesy of Dan Donovan for General Motors |

Backs to the Wall

During the bleak winter of 2008-2009, one could have characterized the auto industry in Missouri as being down to its last strike, or at least with its collective back against the wall. As late as 2005, the state was home to five major motor vehicle assembly plants, with as many as 20,600 auto manufacturing jobs. But by January 2009, there were just three plants left, with another soon to close. The outlook was indeed grim.

So when newly-elected Governor Jay Nixon went before the Missouri General Assembly to deliver his first state-of-the-state address that month, there was little optimism when he thundered “Giving up on the auto industry in Missouri is not an option – and it will not happen under my watch!” A state with the moniker “Show-Me State” is by nature a place full of skeptics, and the new governor would have to show his new constituents before they believed. He actually started doing that before his prophetic words to legislators.

On his first full day in office, Nixon signed an executive order establishing the Missouri Auto Jobs Task Force, a body assigned to develop strategies to create jobs and bring next-generation vehicle production to the state. The report was delivered to Nixon later during the year, with one of the key recommendations concerning the identification of current economic incentives policies and legislative actions needed to help create and retain automobile manufacturing jobs. The report’s recommendations were quickly put into action.

Over the course of several months, Nixon and his economic development team worked closely with the leadership at Ford and GM, including face-to-face meetings in Detroit with CEOs Alan Mulally and Dan Akerson, respectively, to develop a plan that would keep the two industry giants in Missouri for generations to come. The result was the Missouri Manufacturing Jobs Act.

|

| Missouri Governor Jay Nixon |

Coming Through in the Clutch

With competition beckoning from other U.S. states for Missouri’s highly sought-after auto manufacturing jobs, Governor Nixon and the state’s general assembly got the big hit when it counted most.

In June 2010, Nixon called the state legislature back to the state capitol in Jefferson City to convene a special session aimed at strengthening Missouri’s automobile manufacturing industry. With Ford finalizing decisions about restructuring operations and locating production lines, and other states like Michigan aggressively pushing proposals to win the jobs at its plant outside Kansas City, Nixon saw the urgency in passing legislation that would help the Show-Me State bring next-generation vehicle production to Missouri.

“As America’s auto manufacturers reconfigure their operations to produce the vehicles of the 21st century, it is absolutely critical that we are able to compete for the auto jobs of tomorrow,” Gov. Nixon said. “The Missouri Automotive Manufacturing Jobs Act will give us the ability to bring cutting-edge automotive jobs to our state, and I call on the Missouri General Assembly to send this important bill to my desk.”

The Missouri legislature answered that call on July 14, passing the bill that was officially signed into law by Nixon on July 15.

The Missouri Automotive Manufacturing Jobs Act allows qualified manufacturing facilities or suppliers that bring next-generation production lines to Missouri to retain withholdings taxes typically remitted to the state. To be eligible for these incentives, manufacturers are required to make a substantial capital investment in production capacity and put people to work. Incentives are triggered only after a company had made a firm commitment for that investment and workers were on the job. Strict requirements would force a company to repay the incentives if that commitment were not upheld. The total amount of incentives available under the act is capped at $15 million a year.

What the legislation has done is lead to results. The hard work and close relationship forged between Missouri’s leaders and the leadership at Ford and GM officially came to fruition during the fall of 2011.

First, Ford’s October 21 announcement of $1.1 billion in new investment at its western Missouri plant, and its plan to create 1,600 new jobs at the facility, was a cause for celebration in and of itself. The company will be adding a second shift at the long-time Claycomo facility to build the F-150, the most popular pick-up truck in the world, while also beginning production of the full-sized Transit van.

But GM’s announcement just a mere two weeks later of its new $380 million investment into its Wentzville plant in eastern Missouri, with its creation of another 1,660 new jobs to build the Chevrolet Colorado, amounted to the state hitting its second straight grand slam.

Both impressive expansions and new investment were spurred by incentives under the Missouri Manufacturing Jobs Act, which has become exactly what Missouri’s leaders envisioned: a tool to both maintain and strengthen the Show-Me State’s historical position as a leader in the U.S. auto industry. A place Nixon says the state will remain now and forever.

“It is no accident that the rebirth of the U.S. auto industry is starting here in Missouri,” he said. “For generations, Missouri workers have led the way, with their heads, their hands and their hearts. Today, Missouri’s auto workers are once again leading the way, for our state, our country, and our world. This is our moment, and together, we will make the most of it.”